“The record is saying, ‘You’ve got to love life as much as you can, and if something tears some of that away from you then that’s ‘The Soft Bulletin’”

The Flaming Lips faced a pretty uncertain future at the turn of century. It had been a weird decade. But then, weird is just what they do.

After four arty and wonky psych-rock albums were released independently to much acclaim in the late ’80s, they found themselves signed to Warner Bros Records in 1990, back when cigar-chomping record execs were starting to turn grunge and the ‘Alternative Nation’ into big bucks. Alas, these Oklahoma stoners were anything but a cash cow.

Buoyed by the runaway success of college radio banger ‘She Don’t Use Jelly’, 1993’s ‘Transmissions From The Satellite Heart’ finally threatened to catch a little attention and sold a respectable amount, but beyond that their numbers left them in the limbo that they could be dropped at any given moment. Not that they gave too much of a shit.

“We were never that comfortable with the world paying attention to us – especially being on Warner Bros,” frontman Wayne Coyne tells NME. “There was this world of making music videos and needing to sell records and play big concerts – that just wasn’t something that we thought we were very good at.”

A lot of bands in their shoes would have thrown together a couple of quiet-LOUD-quiet-LOUD blasts of late night MTV fodder to keep the moneymen happy, but that would have been the easy way out. While their alt-rock peers were selling out stadiums, the Lips set up a bunch of guerrilla gigs in car parks with frontman Wayne Coyne yelling through a megaphone while messing around with pre-recorded sounds on cassettes played through boomboxes with the help of 40 volunteers.

Guitar wizard Ronald Jones had quit the band due to his agoraphobia and frustrations around the spiralling heroin habit of bandmate Stephen Drozd. Without their guitarist and bored of the post-grunge landscape that surrounded them, they shunned rock from their sound. Instead, they injected some steroids into their boombox show concept to create 1997 “album” ‘Zaireeka’: an art rock experiment of four discs of music that could be played separately, all at once, or in any combination. It was nuts, and their increasingly dubious record label took quite a bit of convincing to put it out.

The hardest part of ‘Zaireeka for them was recording it,” the band’s manager once said in a documentary. “For me, it was getting Warner Bros to put it out.”

They promised to do “a proper record” after “the crazy record” all on one budget.

image: https://ksassets.timeincuk.net/wp/uploads/sites/55/2019/05/GettyImages-688553398_FLAMING_LIPS_2000-1024×650.jpg

The Flaming Lips, in 1999. Credit: Gie Knaeps/Getty Images

With Warners’ interest waning, the follow-up record to ‘Zaireeka was a bit of ‘do or die’ moment, but they also had pestilence and tragedy to contend with. During early sessions for the record, doctors told Drozd that they might have to amputate his whole hand due to what he said was a freak spider bite from the poisonous “fiddleback” (he later admitted it was more likely an abscess from where he’d injected heroin into his hand). The same few months also saw bassist Michael Ivins have a brush with death in a car crash in Oklahoma City when stray tyre barrelled into his car and forced him off the road. Then, Coyne lost his father to cancer.

Liberated by their indulgences on ‘Zaireeka’ and with newfound view on mortality, they emerged with 1999’s bittersweet ‘The Soft Bulletin’ – a symphony of strings, machines and synthetic sunshine. The single ‘Waitin’ For A Superman’ is Coyne coming to terms with the fact that a miracle to save his father was not forthcoming, ‘The Spiderbite Song’ is child-like lullaby of love from Coyne to his bandmates in the wake of their recent near-misses, ‘Feeling Yourself Disintegrate’ admits that “life without death is just impossible” but worth it for love all the same, and ‘Race For The Prize’ is the glorious set-opener telling of two scientists willing to sacrifice everything to save the world. At the very least, they’d saved themselves.

The Flaming Lips had set their existential musings to what sounded like a cinematic, sci-fi sequel to The Beach Boys’ ‘Pet Sounds’. It worked. The mad scientists finally cracked the mainstream, the critics gave it top marks, and NME named it as 1999’s Album Of The Year.

To give the album the theatre it deserved, the subsequent live shows shaped The Flaming Lips into the blood-splattered, balloon-loving, laser-fuelled, animal-friendly, festival headlining freakshow inside a giant bubble that you see today. The band who made the soundtrack for Spongebob Squarepants. The band who got together with Miley Cyrus to explore her freakier side. The band who released one album inside a gummy skull and another featuring Nick Cave’s actual blood. The band who can do what the fuck they want, and all thanks to the gift that is ‘The Soft Bulletin’.

To celebrate the album on its 20th anniversary, we caught up with Wayne Coyne to talk over the seismic impact that the record had on his life and thousands of others.

Hello Wayne. Do you feel a weight around the legacy of ‘The Soft Bulletin’?

“Only now. I don’t think we would have liked that in the beginning. I don’t think we could have made the album if we thought that was going to happen. We’re not those young, innocent guys getting ready to make that transition that ‘The Soft Bulletin’ was about.”

But you see it for what it is now?

“Now we do. Maybe 20 years is a long time to have figured it out, but now the music affects us too. We made it so long ago that there are no longer those muscle memory triggers of the struggles and the failures and all that it takes to make music like that. Now I just hear it and I’m like, ‘Who the fuck made this record? This is a good record! This is cool!’”

“We’re not those young, innocent guys getting ready to make that transition that ‘The Soft Bulletin’ was about” – Wayne Coyne

It’s a life-affirming record that a lot of people have a very profound connection to. Is that a headfuck?

“Yeah. We’re great ambassadors to being the ones who get to stand there and sing these songs, but it’s a strange world. ‘The Soft Bulletin’ is catching us in the transition of going from one mode to another. We knew that at the time; that we weren’t the same people who’d started to make this thing. We knew we couldn’t make another record like that. All we could do was make another record of how we felt at the time.”

A lot has been said over the years that this could very well have been your last album.

“I think ‘Zaireeka’ really freed us up. We got signed to Warner Bros in the early ‘90s, wanting them to succeed but not knowing how to do that. We knew there was a limit to that kind of freedom and we pushed that to the absolute limit when we made the ‘Zaireeka’. We were just looking at the future going ‘If we’re gonna make a record like ‘The Soft Bulletin’, why would they keep us?’”

Was there a very real threat of getting dropped?

“We started to make ‘The Soft Bulletin’ while being very realistic that it could be the last one we ever made. We weren’t event pretending to be aware of commercial viability. We thought that if nothing else, it would stand for us. Nobody can control the music industry but we could control making the record we wanted to. If they kick us off the label then that’s that. There wasn’t a fear of failure, we just had to be sure that we wanted to make it. Once we had that, it gave us even more confidence.”

It also seems like true rebirth of the band. From there on, you’re almost unrecognisable as the band who made ‘She Don’t Use Jelly’.

“When ‘The Soft Bulletin’ came out, we really were just completely oblivious to being like a rock band that people were used to. I didn’t know if it was going to go anywhere. We were starting to play shows and that’s where our originality really surfaced for the first time. We weren’t trying to be a normal band. We didn’t even know what a band like us should be like.”

“There wasn’t a fear of failure, we just had to be sure that we wanted to make it.” – Wayne Coyne

So the live shows just became more instinctual?

“We were throwing confetti around, I’d pour blood on my head, and we knew that if you’d come see us we could entertain you. I didn’t know if we were gonna look like any other band you’d seen before but we were going to try and entertain you and see how it goes. Who’d have ever thought that would work? There’s no marketing and there’s no plan.”

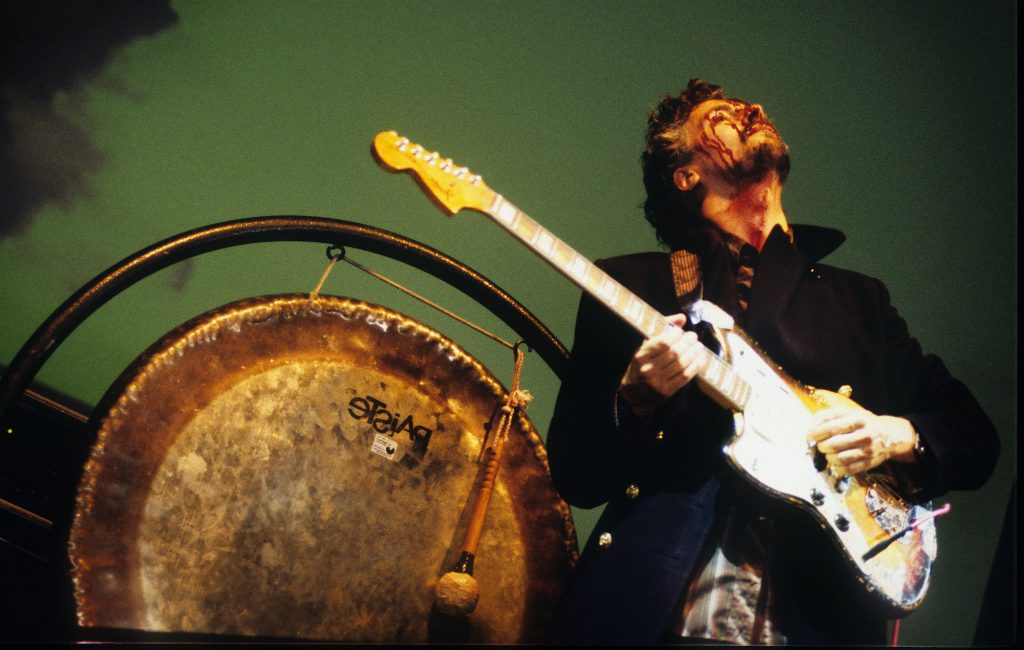

image: https://ksassets.timeincuk.net/wp/uploads/sites/55/2019/05/GettyImages-688553408_FLAMING_LIPS_2000-1024×650.jpg

The Flaming Lips, live in 1999. Credit: Gie Knaeps/Getty Images

How much would you say that the album owes to ‘Zaireeka’?

“Part of the thing with The Flaming Lips and the strings, the horns, the timpani – there’s a certain authentic drama about it. Though we were using the most modern synthesizers and digital junk that you could get at the time, we were trying to make it sound like it wasn’t a band any more. We wanted it be more of an emotional sound than a band. I think those things we did on ‘Zaireeka’ freed us from being a band.”

Did that just happen or did you have a very ‘anti-band’ attitude?

“We were trying to say we’re not a band that plays drums or has bass players or guitar players. It was just going to be the sound that accompanied my singing. We didn’t want you to envision what you get when you imagine Led Zeppelin with John Bonham and Jimmy Page and whatever. We didn’t want you to envision anything. You just heard it as music. Whatever you envisioned was this other world.”

But the concept didn’t catch the world’s attention?

“I don’t know if ‘Zaireeka’ did that for other people but it allowed us to just make music. It was just such a technical mindfuck. Some of the best songs on ‘The Soft Bulletin’ were rejects from ‘Zaireeka’ because they just didn’t work. ‘Race For The Prize’ was a reject from ‘Zaireeka’. That’s how insane we were.”

Did you realize the potential what you had on your hands?

“That’s the height of being so obsessed and fucked up on these ridiculous ideas. We were no longer hearing it as music. It wasn’t music, it wasn’t lyrics, it wasn’t chord structures. We came down from that and we realised that we had these insane tracks that were the best songs we’d ever come up with. Just three months earlier, they were the rejects that we didn’t see the use in putting out. That’s the truth of it. You really do have to be completely in love with what you’re doing and see where it gets you. It doesn’t always get you where you want to go, but it definitely gets you somewhere.”

“It speaks to a certain sensitive person. I don’t think it speaks to a Foo Fighters’ kind of audience.” – Wayne Coyne

The band were dealing with a lot of loss and demons at the time. 20 years later, what would you say the resounding message is of ‘The Soft Bulletin’?

“It speaks to a certain sensitive person. I don’t think it speaks to a Foo Fighters’ kind of audience. When Steven, Dave Friddmann [producer] and I we were making it we were grappling in our minds with the idea that the world is a happy and beautiful place. You know; you’re optimistic and all of this is work for you in your young life. The longer you keep going forward into this beautiful place you start to realise that it’s not really a beautiful place. Bits of it are full of unfair and horrible things. It’s a shift of going from this innocent person saying ‘Anything is possible, everything is beautiful – bring it on. I love life so much’, then having to say ‘Well if you love life so much, what if some of it dies? What are you going to do now?’”

And do you feel that the record answers that question?

“The record is saying, ‘You’ve got to love life as much as you can, and if something tears some of that away from you then that’s ‘The Soft Bulletin’. It’s ‘Oh no’. If you live, you love and you absolutely throw yourself into it then what if it dies? What choice do we have? Do we live half a life because we don’t want to get hurt so much? Do we love half a love because if might lose it?”

So the bad is ultimately worth it for the good?

“That’s a real thing. We used the words ‘soft’ and bullet’ and ‘in’. It’s like part of you is being executed by something that doesn’t hurt you like a real bullet. It’s a soft bullet. ‘The Soft Bulletin’ is giving you this gentle message. That’s why I say it’s for sensitive people. I think for a lot of people it doesn’t matter that much. Your mind can be filled with other things, but if you’re an innocent person and your mind has that deep connection to love, beauty and family, then you have a lot to lose. You may lose yourself. You may be so devastated by your love for it that you don’t want to live. Somewhere in there ‘The Soft Bulletin’ was just saying, ‘I know, I know what you mean’. That’s enough. There’s a Daniel Johnston song that goes ‘To understand and be understood’. There’s something in there that let’s you go to the next day.”

“If you live, you love and you absolutely throw yourself into it then what if it dies? What choice do we have?” – Wayne Coyne

You can still hear echoes of ‘The Soft Bulletin’ in a lot of today’s big psych bands. Do you often notice your influence in other artists?

“No, not really. I think people will point it out and go, ‘Oh there’s Tame Impala or MGMT’ but really to us it was the other way around. We loved their music before they even knew who we were. If someone compares Tame Impala or MGMT to us then that’s great. I think they make great and original, crazy music. I’m glad that people would put us in that category, but I don’t think that Steven and I would ever think of it in that way.”

Flaming Lips’ Wayne Coyne

You’ve got these anniversary shows coming up. Do you feel as if you might do this for ‘Yoshimi Battles The Pink Robots’ or your other album?

“Yeah, I do. It’s something that I wanted when I was growing up. I never got to see Pink Floyd or The Beatles, but in my dreams I would have loved to have seen The Beatles play ‘The White Album’. Who wouldn’t, you know? I think we’re very capable of that stuff now. The guys in the group with the technology and all of the shit we have available to us now, it really is great to sing these songs with the arrangements and those kind of sounds.

“As it gets closer, I think we probably will. I don’t know if it has the same emotional power as ‘The Soft Bulletin’, but we’ve played ‘Do You Realize??’ and some of those songs every night since they came out so those songs are always with us. Some it is weird stuff that we’ve never played. But I think so. We like it where we’re not doing ‘the big overview’ of The Flaming Lips’ festival set and it feels different from last night.”

For ‘The Soft Bulletin’ shows, will you be reimagining the songs?

“There’s probably a perception of The Flaming Lips that is probably like The Grateful Dead or Phish or a jam band or something. You know, that we take a song that you know that’s 20 minutes’ long and it becomes a 30-minute jam session. But we really don’t do that. I like it when Jimi Hendrix or Miles Davies does that but I don’t like it in particular for us. With a record like ‘The Soft Bulletin’, that’s not what the music is. We’re always very careful to do the music as well and as familiar as it can be. I know just by talking to people in the audience that they have some very powerful connections to these songs. I’m always aware of that with songs from ‘The Soft Bulletin’.”

The band will return to the UK to perform ‘The Soft Bulletin’ anniversary tour in September.